by Audrey, Charles and Faye Henderson, April 2012

John Henderson (1791-1864) and Elizabeth Brown (1797-1873) Their Children and Families

Preface

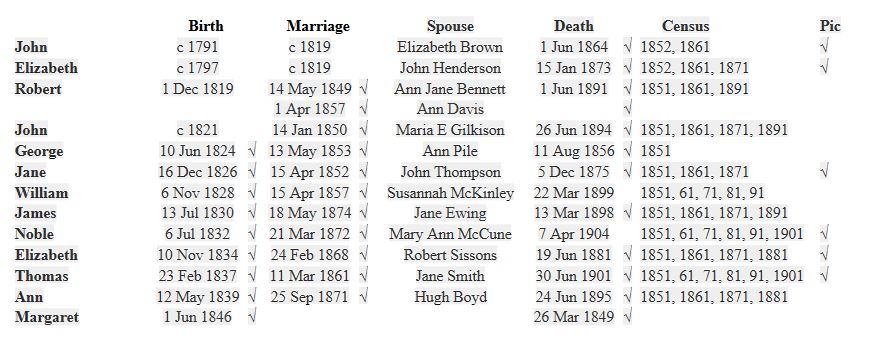

The Henderson’s family history was initially undertaken by my cousin Charles Henderson. Charlie conducted his research prior to the age of the internet, and hence had spent numerous hours in libraries and archives. Charlie concluded his history in 1993. Since that time, my identical twin sister and I have undertaken to continue his magnificent work and have been doing so since 2007. This Henderson history commences with John Henderson, circa 1791, who arrived in Quebec sometime between 1821 and 1824. No substantive evidence can be found from any Passenger or Immigration lists of the time as to a specific date of arrival or ship name.After each family mentioned, a list of their children appear, and dates and names, if available, are provided. After the birth, marriage and death columns, a check mark indicates a record exists. A date which appears under the Census column indicates the Census record has been located for the person named in the extreme left hand column. To the right of the Census column is a column titled “Pic” – a check mark in this column indicates a picture of the tombstone exists.In the Appendix is a list of all persons mentioned within the document and their relative dates of birth and death. Within the body of the report the dates for spouses (with the exception of John Henderson and Elizabeth Brown’s children) are not identified. However, these are identified in the Appendix.The result of our work is captured under Ancestry.ca; including documents, stories and photos are captured on the site. Although we have strived for thoroughness and excellence, there may be misstatements or inadvertent incorrectness. Any comments, substantiated corrections or questions are kindly appreciated. We would be pleased to add any new family members, stories, etc. with due credit. Our efforts as well as this document should be considered a work in progress. This report will be updated periodically. As a first edition, the report only captures and documents the lives of John Henderson (1791-1864) and Elizabeth Brown (1797-1873) and their children’s families.

Introduction

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, large numbers of English and Scottish tenant farmers were transplanted to Ireland in an attempt to strengthen the British presence throughout that island. Most of these emigrants left their native land reluctantly. Evicted from Scotland during the Clearances, and from England by the chronic, rural population explosion, they found that their new life in Ireland was as difficult as their previous existence in England and Scotland. Lacking the financial means and the skills to do otherwise, many of them were destined to remain tenant farmers at the mercy of the local gentry. Although, in most cases, their standard of living was substantially better than that of the indigenous Irish population, they still faced enormous problems as they attempted to survive and to prosper on marginally productive land.

By the early nineteenth century, as conditions in Ireland worsened due to disastrous overcrowding and reduced agricultural productivity, severe changes were made to the local tenancy laws. As a result, mass evictions commenced. Thousands of families, both Protestant and Catholic, were expelled from their homes and their lands seized. Many of these dispossessed sought relief in the flourishing industrial centres of London, Manchester and Liverpool. Many more looked across the Atlantic Ocean, towards British North America and the United States, where they perceived an opportunity for a more tolerable existence.During the thirty years between the end of the Napoleonic Wars (1815) and the outbreak of the Great Irish Famine (1845), half a million Irish men, women and children immigrated to British North America. Not all of them had suffered the loss of their Irish lands, and many of them brought adequate funds to begin their new life in America. Mostly farmers, labourers and tradesmen, the majority of these Irish immigrants were descendants of those English and Scottish Protestants who had earlier settled in the northern Irish province of Ulster. Once in North America, they found that the abundance of free or inexpensive land allowed them to return to their previous occupation as farmers. Rural communities with a concentrated Irish population came into existence in several parts of what is now eastern and central Canada.In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Scotland, like Ireland, also experienced a mass emigration of citizens to British North America. Between approximately 1770 and 1870 over 200,000 Scottish settlers arrived in Canada. Unlike Irish immigration, which tended to be highly disorganized and, in many cases, a desperate attempt to escape the horrendous economic conditions in Ireland, Scottish immigration was usually a structured and organized movement of families who were often more financially secure than their Irish counterparts. Many Scottish immigrants arrived in North America through resettlement schemes sponsored by the British government or as clients of private land companies. As well, a large number of Scottish soldiers who served in North America during the war of 1812, or in Europe during the Napoleonic Wars, accepted land in Canada as settlement for their military service. Again, like the Irish, Scottish immigrants were usually farmers who tended to settle alongside other Scots, particularly in Nova Scotia and on the north shore of the St. Lawrence River in present day Quebec and Ontario.By the mid-nineteenth century, the early Scottish, Irish and English immigrants to British North America had become adjusted to their new surroundings and were beginning to experience a limited sort of prosperity.Their struggles with the land appeared to be over as they expanded their farms and continued to build and to improve on their somewhat primitive infrastructure (roads, bridges, schools, etc.). Yet, for many of these immigrants, the search for economic security was not yet complete. In possession of only marginally productive land, they found that by the mid 1800s they could no longer adequately support themselves and their expanding families. As a result, a flurry of movement began as settlers left their farms in search of better land. In response, the government increased the amount of land available for settlement by opening up large sections of the country’s interior. This, in turn, provided the means for greater integration among the various ethnic groupings, as an ethnic mixing occurred during the scramble for new land. By the beginning of the twentieth century, this integration was well on its way to creating the Canada we know today.

John Henderson and Elizabeth Brown

John Henderson, born County Fermanagh, Province of Ulster, Ireland, circa 1790, was undoubtedly a descendant of the Scottish settlers who arrived in Ireland during the mass migrations of the previous centuries. He was, in most respects, typical of his time and circumstances. Raised on one of the great estates as the illiterate son of a tenant farmer, he faced a future with few prospects and many disadvantages. However, when still a young man, he availed himself of one possible opportunity. He became a soldier in the British Army.At the time of John Henderson’s enlistment, Britain was at war with France. As a result, John was probably a participant in several engagements in that conflict. He may have served in Spain or Portugal, and quite possibly have taken part in the last field action of war, the Battle of Waterloo (1815). Although the name of the regiment in which John served is not known, there was a large contingent of Irish soldiers present at Waterloo. The ferocity of these Irish troops can best be judged through a comment made by the Duke of Wellington, the British commander at Waterloo. Speaking of his Irish recruits, His Grace is said to have exclaimed: “I don’t know what they will do to the enemy, but by God, sir, they frighten me!”Regardless of where he saw action, once hostilities ceased, John was discharged from military service and returned to the family farm. About 1819, in the local Anglican Church of England, he married Elizabeth Brown, also born in County Fermanagh, circa 1797, the daughter of another tenant farmer. Faced with the responsibility of marriage and parenthood, as well as the declining conditions on the land and the real threat of eviction, John and Elizabeth must have begun to consider other ways to improve their circumstances. As was the practice of the day, when John was discharged from military service he was probably offered either a grant of land in British North America or a specified amount of money as a final settlement for his services. Since there is a space of some years between when he left the army and when he arrived in North America, it is more likely that he chose to accept the money. Although he was described as a “pensioner in Her Majesty’s service” on his death certificate in Lower Canada in 1864, it is possible the military settlement provided the four to six pounds per person which was the amount charged for an ocean crossing.The exact date of John and Elizabeth’s arrival in British North America is not known. However, it is most likely they reached Quebec City sometime between 1821 and 1823, given the location of birth of their eldest sons. The conditions which they faced upon their arrival can best be described by quoting from an official

report published at the time:

“In the year 1822 and 1823, 10,300 emigrants upon the average annually arrived at Quebec. By far the larger proportion of these were little better then paupers. Having paid from four to six pounds for their passage and their sustenance on the voyage, they found themselves destitute on arriving at Quebec; they had neither the means of going upon Crown Land if granted to them, nor of cultivating it. The greater part, if they had money to pay their passage up the St. Lawrence or if they could obtain it by a few days labour at Quebec, hastened on to Upper Canada (Ontario)…..Few remained and became useful and effective settlers in the Lower Province (Quebec)….the proportions of the emigrants…..may be stated at about three-fifths Irish. Of the Irish, scarcely one-twentieth landed with any but a scanty provision of clothes and bedding.”

The extract just quoted is probably an accurate description of the situation in which John and Elizabeth Henderson found themselves. Certainly, they received no grant of land, nor did they travel further inland toward more fertile regions farther west. Instead, by 1824, they had become tenant farmers just a few miles northwest of Quebec City, near the small settlement of Saint Patrick’s Mission. Here occupying a one story frame house, John and Elizabeth would remain for the rest of their lives. Here too the rest of their children would be born, as would several of their grandchildren.

Ste-Catherine de Fossambault was located on the Jacques Cartier River, near the south shore of Lac St.Joseph, and formed part of the Seigneurie de Fossambault. Fossambault, which is today a part of Portneuf County, was one section of a much larger portion of land which, in 1649, was granted to Robert Giffard, the first surgeon in New France. In 1693, after Giffard died leaving no male issue, the land passed to Alexander Peuvret, who called the area Seigneurie de Fossambault, after his mother, Catherine Nau de Fossambault. Leaving no heirs, the land was passed onto Alexander Peuvret’s sister, who was married to Ignace Juchereau Duchesnay. The land was then taken over by their son, Antoine, and then by his son Michel Louis Duchesnay. By 1821, Michel Louis Duchesnay, in recognition of Irish immigrants, established land concessions and the new area was called “St-Patrice”, also referred to as St. Patrick’s Mission, and later it was Ste-Catherine de Fossambault. It was Michel Louis Duchesnay who became John Henderson’s landlord.Under the seigniorial system then in place in Lower Canada, John Henderson could not own his land. However, as long as he continued to live on the property, made regular improvements and was prompt with his rental payments, he could not be evicted. In John’s case, these yearly rents averaged approximately four pounds per annum. Later, when the seigniorial system was abolished (1854), John was free to purchase his farm outright, and would have done so for only a token amount.The Henderson farm, situated on Concession 4, Lot 15, near the village of Ste-Catherine, was located in an area not particularly conducive to agricultural excellence. The rocky and sandy soil was unsuitable for many crops. Still, John and Elizabeth appear to have been relatively successful farmers. At one time, they owned 250 acres, of which 50 acres were under cultivation and 15 acres were in pasture. The remaining land was wooded and, for the most part, remained so during John’s lifetime. In 1861, the Henderson farm was valued at $ 1600, the livestock was valued at $ 200, and the farm equipment was valued at $ 80. The family livestock included 2 horses, 7 steer, 2 cows, a bull, 8 sheep and 2 pigs. Their crops consisted of 3 acres of wheat, 15acres of oats, 5 acres of potatoes and 600 bundles of hay (at 16 pounds each). In addition, the family annually processed 350 pounds of butter, 600 pounds of lard, 300 pounds of beef and 40 pounds of wool.John Henderson died at Ste-Catherine on April 21, 1864. Elizabeth Brown passed away at Ste-Catherine on January 15, 1873. Both are buried in the Christ Church Anglican Cemetery, Valcartier, Quebec.

Although there were a few “Brown” families who lived in the Valcartier area since the early 1800’s, no relationship to Elizabeth has been found.After John Henderson’s death, his son Noble took possession of the farm. Noble eventually increased the farm to 268 acres, of which 132 were placed under cultivation.In a book provided by a Valcartier resident of St. Raymond, called “Our Banyan Tree” by Beulah Warner Russon (Mormon), a story provided by Robert Henderson (1819-1891 – John’s son) indicates that John Henderson’s father’s name was Robert who was born in Ireland circa 1750 and he died in Ireland. He married Ellen Benson and they had at least three children: George, Catherine and John. It is indicated their son,

George, enlisted in the Eonis Killen Orgdons (upon his mother’s second marriage) and was killed in Waterloo. Their daughter Catherine was born in Lent, Ireland, circa 1798 and married James Morrow of Bella Inn, Drenf, Ireland. Ellen Henderson, a widow, remarried John Herniker. John Herniker died in Ireland and his widow died at Jacques Cartier (Valcartier). The book also indicates Robert was born on December 1, 1819 at Enniskillen, Fermanagh, Ireland.

There is probably some truth to the information in the book, but not all of it is accurate as it contains a number of errors, the major ones being some of the names of John Henderson and Elizabeth Brown’s children and other information as well; e.g.: the name of the regiment and names of places have been verified and can not be found.

Catherine Henderson married James Morrow, of Ireland, and of the Seigneury of Neuville, in April 1825. Their marriage certificate is signed Jane Henderson and David Henderson. I have not been able to identify exactly who Jane and David are. (However, there was a married couple, David and Jane Henderson living in Quebec City who had a daughter Jane on June 28, 1821.)

There is reason to question if indeed Ellen Benson, as named in the book, is the mother of George, Catherine and John Henderson. I have found no record of her death. Based on the naming conventions and traditions of theday, intuition strongly suggests their mother was a “Jane”. John Henderson’s (1791-1864) first born daughter is called Jane; Catherine Henderson’s (1798-1894) second daughter is Jane (first is Ann), Robert Henderson’s (1819-1891) first born is called Jane; George Henderson’s (1824-1856) daughter is Ann Jane; William Henderson’s (1828-1899) second daughter is Jane (first is Elizabeth); James Henderson’s (1830-1898) only daughter is Ann Jane; Noble Henderson’s (1832-1904) daughter is Mary Jane; Elizabeth Henderson’s (1834-1881)first daughter is Ann and another is Jane; Thomas Henderson’s (1837-1901) daughter is Jane; Ann Henderson’s(1839-1895) daughter is Eliza Jane. On numerous occasions during that era, children were named after their grandparents and parents, and deceased siblings. The Henderson family certainly followed this tradition throughout the 1800’s.

The following children were born to John Henderson and Elizabeth Brown and their names appear after the parents.

Robert Henderson, Ann Jane Bennett and Ann Davis

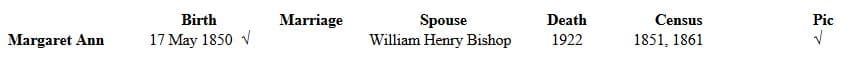

As noted above, the book “Our Banyan Tree” by Beulah Warner Russon notes Robert was born on December 1, 1819 at Enniskellen, Fermanagh, Ireland to John Henderson (1791-1864) and Elizabeth Brown(1797-1873). His death certificate indicates he was a farmer of St. Bazile. He was buried at the Bourg Louis Church of England graveyard at the age of 72. His death certificate is signed by his daughter Margaret Ann Henderson (1850-1922) and John Henderson (I suspect his brother (1821-1894)). Robert Henderson married Ann Jane Bennett on May 14, 1849. Ann Jane was the eldest daughter of George Bennett (1809-1872), from Armagh, Ireland, and Jane Austin (1829-1874) of Dunn, Ireland, who was born about 1833. Robert and Ann Jane’s daughter Margaret Ann Henderson was born on May 17, 1850. Ann Jane Bennett died on November 26, 1851. Margaret Ann was raised by Robert’s parents, John Henderson (1791-1864) and Elizabeth Brown (1797-1873), while Robert lived and worked in Quebec City. The 1851 Census lists Robert and Margaret Ann at his parents’ residence and Robert is identified as a widower and working in Quebec.George Bennett (1809-1872) and Jane Austin (1829-1874) also had a daughter born on November 25, 1852 andcalled her Ann Jane; she was born almost one year to the day of her eldest sister’s (Ann Jane – 1833-1851) death. In addition, George Bennett and Jane Austin had a son Thomas born on May 1, 1842. However, he must have died in the first year and a half of his birth as they named their next child Thomas, born on October 23, 1843.Robert Henderson (1819-1891) and Ann Jane Bennett (1833-1851) had one daughter as seen below. Robert re-married on April 1, 1857 to Ann (Nance) Davis (1823-1892) on April 1, 1857. Ann Davis was the daughter of Thomas Davis (1789-1872) and Catherine Pritchard (1796-1872).

John Henderson and Maria Emilie Gilkison

John Henderson was born in Ireland in or about 1821, the son of John Henderson (1791-1864) and Elizabeth Brown (1797-1873). He married Maria Emilie Gilkison (1832-1903) in Bourg Louis on January 14, 1850 and resided there all his life. Their marriage certificate is witnessed by Jane Henderson (likely his sister, 1826-1875)and William Morrow (likely his cousin, 1827-1911). Census records note he was a farmer. John’s death certificate indicates he died at about age 75 and is buried at the Bourg Louis Church of England graveyard.Maria Emilie Gilkison (1832-1903) was born circa 1832 in Ireland to Robert Gilkison (1789-1872) and Martha Curry (1795-1871). According to the Gilkison family, Robert Gilkison died on 30 Jan 1872. Martha Curry died between 1861 and 1871 as the 1871 Census records Robert as a widower at that time.After John Henderson’s (1821-1894) death, Maria Emilie Gilkison (1832-1903) and her son James lived together.Maria died at 128 Wellington Street North in Hamilton, Ontario on April 11, 1903. This was her son James’ residence at the time. Maria is interred at the Bourg Louis Church of England graveyard.

John Henderson and Maria Emilie Gilkison had the following children:

George Henderson and Ann Pile

George Henderson was the first child born to John Henderson (1791-1864) and Elizabeth Brown (1797-1873) in Lower Canada on June 10,1824. George married Ann Pile (1835-) on May 13, 1853 and they had two daughters. George died very young, on August 11, 1856, when his second daughter was only six months old. George’s death certificate is signed by Robert Henderson, (presumably his older brother, 1819-1891). Ann Pile was born on December 1, 1835 to Henry Pile (1802-1898) and Jane Griffith (1796-1863), both from Ireland. She remarried on March 29, 1858 to William Williamson (1832-1892) and they had at least eleven children together.Children of George Henderson and Ann Pile:

Children of George Henderson and Ann Pile:

Jane Henderson and John Thompson

Jane Henderson was born to John Henderson (1791-1864) and Elizabeth Brown (1797-1873) in Lower Canada on December 16, 1826. Jane married John Thompson (1826-1897) of Ireland on April 15, 1852. She died at the young age of 49 on December 5, 1875 and is buried with her husband and her son Francis (1855-1874) at St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church Cemetery in Valcartier. Three other children died at a very young age, but they are not named on the tombstone.Of special note is an entry in the Valcartier Church of England registry which indicates: “Thompson received into the Church: son of John Thompson of Ireland in the District and County of Quebec and ofJane by her maiden name Henderson was born on the twenty eighth day of June….”. The son’s name isnot provided.Jane’s sister Elizabeth (1834-1885), who only married in her mid-thirties, lived with Jane and John Thompson for some years.

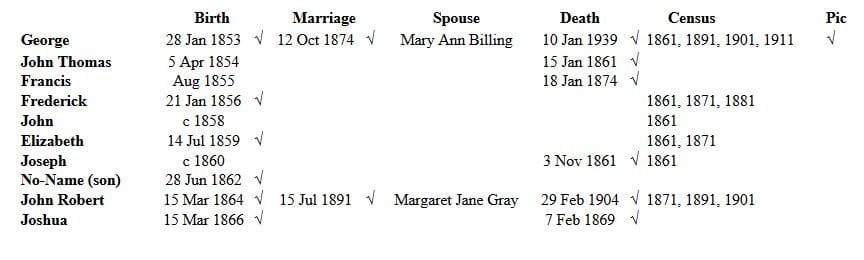

Jane Henderson and John Thompson had the following children :

William Henderson and Susannah McKinley

William Henderson was born to John Henderson (1791-1864) and Elizabeth Brown (1797-1873) on November 6, 1828. He married Susannah McKinley on April 15, 1857, at the Church of England at Sainte-Catherine. Susannah was the daughter of Andrew McKinley (1789-1881) and Sarah McCune (1803-1885), both of the Parish of Loughgilly, County of Armagh, Ireland. Susannah was born in Lower Canada on May 4, 1829.There were two females of the same name, Susannah McKinley, who both lived in the area of Valcartier, at the same time, in the 1800’s. However, one Susannah McKinley, born in Lower Canada, married William Henderson (1828-1899). The other Susannah McKinley, born in Ireland, married William McPherson.The first two born daughters of William Henderson and Susannah McKinley were named after their respective grandmothers, Sarah and Elizabeth. Their first two born sons were named after their respective grandfathers, Andrew and John.After the marriage of William and Susannah, they took up farming at Concession 1, lot 1 near the village of Valcartier, not far from Susannah’s parents. At the time that William and Susannah went to live on their farm at least 90 acres of it was clear of trees and brush, indicating the land had been previously cultivated. Initially, only eight acres was placed under cultivation and a further 82 acres was pasture. Gradually, over a period of a few years, they increased their cultivated acreage and, in time, even purchased another thirty acres of land. They came to own two hundred and seventy acres of land, of which one hundred acres were eventually placed under cultivation. The average yearly yield of crops was 900 bushels of oats, 900 bushels of potatoes and 15,000 bundles of hay (each bundle weighing sixteen pounds). In addition, the farm produced almost 350 pounds of butter and 200 pounds of barreled beef annually.While William and Susannah occupied their farm, they lived in a one story frame house. Also erected on the property was a barn and an adjoining stable. The barn and stable held the family livestock – 2 horses, a colt, 4 cows, 3 pigs and 2 sheep, from which they obtained twelve pounds of wool. Although they themselves had no formal education, William and Susannah were obviously anxious that their children should be educated. Each child received a basic education at the local school in Valcartier. It is probable they could spare their children the arduous tasks associated with farming because they had adult help. For several years, William’s brother Thomas (1837-1901) lived with them and assisted in the heavy farm labour. As well, they were able to afford the services of a local farm girl, Maureen Quinn, who would have performed numerous chores.

Although William and Susannah most likely worked hard to make their farm a success, it is most probable their soil was of poor quality and was deteriorating with each passing season. Had they purchased virgin land it might have been possible to successfully operate for one or two more decades.By 1875 it appears that many of their neighbours were leaving their farms most possibly in search of other ways to make a living. So too did William.By the late 1870s, the railway boom was in full swing in Eastern Canada. Every city, town and village demanded its own rail line. William Henderson lived in a location that was ideally suited to profit greatly from this consuming interest in railways.Prior to 1870, Quebec City did not have its own rail line. Any traveler wishing to reach the city by rail could only go as far as Levis, on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River, and across from Quebec City.Once Quebec received its own line in 1870, there was an immediate rush to organize spur lines which would reach north, east and west of the city. About this same time, William and Susannah decided to sell their farm, move their family to Quebec City, and find jobs for William and his older sons as railroad men. In the late 1870’s they left their farm and took up residence, in a rented house, in the section of Quebec City known as St. Roch.By the mid and late 1880s, railway construction in and near Quebec City had reached its saturation point. However, west of Quebec City it was a different story. The Grand Trunk Railway was in the midst of a constructing a line along the north shore of the St. Lawrence River, from east of Montreal, and west toward the Ottawa valley. William gained employment on this new line, and he and his family left Quebec,following the rail line west until, by 1890, they were residents of the small village of Wakefield, Quebec.Wakefield, a farming and logging community situated on the Gatineau River, about thirty miles north of the city of Ottawa, was then the northern terminal for the newly created Gatineau Valley Railway which in time, would extend north from Hull, Quebec to the Gatineau River village of Maniwaki.Living in rented premises in Wakefield, William and his sons worked on the northern extension of the Gatineau Valley Railway, as it snaked its way north toward the small village of Gracefield, Quebec. Aswell, for a short while they were employed in the construction of the Pontiac and Pacific Junction Railway(known locally as the “Push, Pull and Jerk”) which was pushing its way west into the heart of Pontiac County, Quebec.

By the mid 1890’s, William Henderson was becoming too old for the heavy work involved in railway construction. Accordingly, he and Susannah, along with the children who still resided with them, left Wakefield. They moved across the Ottawa River to the city of Ottawa, where, by 1897, they were living at 88 Kent Street. William opened a small lumber retail business in a wooden addition which adjourned the family home. A year later, William and Susannah were forced to vacate this rented house when it was taken over by the Massey-Harris Company. They moved to other rented premises at 549 Wellington Street, at which time William gave up his short career as a lumber merchant and became a railway”contractor”. By 1899, he and Susannah were living in Hull, Quebec with their son Andrew (1863-1942) and his family. On March 22, 1899, William died in his son’s home at 180 Alma Street, Hull, Quebec and was buried two days later, on March 14th in St. James Anglican Cemetery, Hull.By 1901, after the Great Ottawa-Hull Fire of 1900, Susannah Henderson had moved back to Ottawa where, by 1906 she was lodging in rented rooms at 166 Division Street in the old Le Breton Flats area. On February 15, 1907, at 8:40 am, Susannah died at her residence. A few days later she was buried next to her husband in St. James Cemetery.

Susannah McKinley’s sister, Mary Ann (1834-1918), married Adam Mather (1834-1892). Mary Ann and Adam Mather’s tombstone rests at St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, Valcartier. On the side of their tombstone is an inscription for William Henderson and Susannah McKinley’s daughter Elizabeth which indicated Elizabeth died on August 26, 1879 at the age of 19 years, 9 months.Their son Adam Henderson (1872-) married his first cousin, Jane Sissons (1872-), daughter of Elizabeth Henderson (1834-1881) and Robert Sissons (1848-1916).

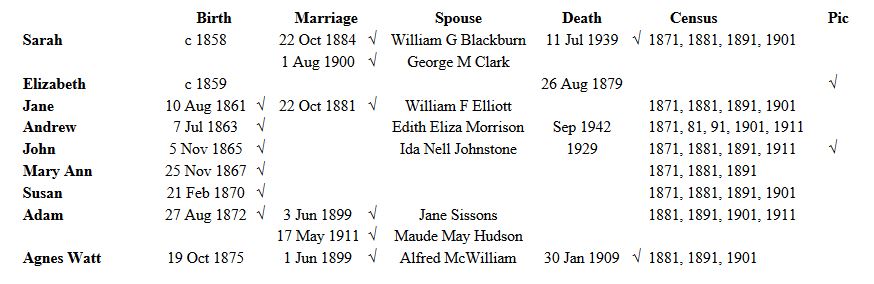

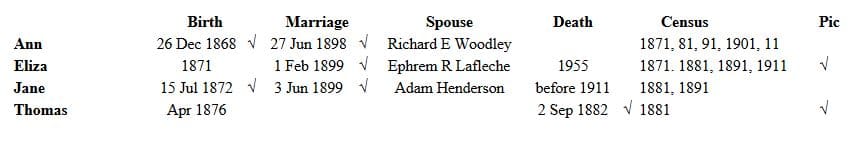

William Henderson and Susannah McKinley had the following children:

James Henderson and Jane Ewing

James Henderson was born in Lower Canada on July 13, 1830, to John Henderson (1791-1864) and Elizabeth Brown (1797-1873). He married Mary Jane Ewing, also born in Lower Canada on August 29, 1844 to Thomas Ewing (1814-1890) and Jane Duncan (1807-1890), both from Ireland. James was 43 years old and Jane 30 years old when they married on May 18, 1874. During their married life they lived at St. Ambroise de la Jeune Lorette, not far from her parents.James died on March 13, 1898, his death certificate is signed by Thomas George Henderson (1877-1936), his son, and is buried at the Valcartier Anglican Church Cemetery.Jane Ewing continued to live at St. Ambroise after her husband’s death. She died on March 20, 1936 at the Jeffrey Hale’s Hospital at 92 years old. Her death certificate is signed by George Henderson (1909-1975) (presumably her grandson) and she is buried at Christ Church Cemetery, Valcartier.Both Jane Ewing and her son Thomas George (1877-1936) died within five days of each other at the Jeffrey Hale’s Hospital.James Henderson and Jane Ewing had four children, only one of which survived past adulthood. Their youngest son John Duncan (1881-1893), who died at 12 years old, was named after his older brother of the same name who died when he was 2 years old. Their daughter Anne Jane (1878-1882) died when she was 4. Their son Thomas George Henderson (1877-1936) married his first cousin, Eliza Jane Boyd (1875-1954), son of Ann Henderson (1839-1895) and Hugh Boyd (1834-1922).

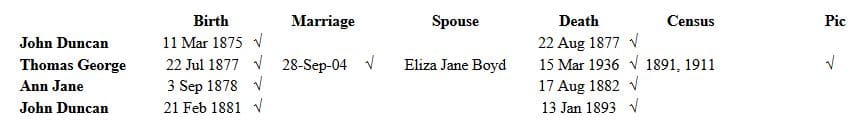

James Henderson and Jane Ewing had the following children:

Noble Henderson and Mary Ann McCune

Noble Henderson was born on July 6, 1832 to John Henderson (1791-1864) and Elizabeth Brown (1797-1873). After his father’s death in 1864, Noble took possession of the family farm. At this point, Noble was still a bachelor. However, on March 21, 1872, at the age of 40, Noble married Mary Ann McCune (1850-1919) who was 22 years old.Mary Ann McCune was born on September 1, 1850 to John McCune (1816-1900) and Mary Davis(1827-1900). Mary Davis was the sister of Ann Davis (1823-1892) who was Robert Henderson’s(1819-1891) second wife. Mary Davis’ parents were Thomas Davis (1789-1872) and Catherine Pritchard (1796-1872). Noble Henderson and Mary Ann McCune were farmers their entire lives. They moved to Hull some time after 1882. Noble died on April 7 1904. Mary Ann died on December 3, 1919, and at the timeshe lived at 12 Percy Street. They are both buried at the Bellevue Cemetery in Hull. In addition to their names and particulars on their tombstone, so too is the name and particulars of six of theirfifteen children: Mary Jane, John, George, Elizabeth, Olive Reed and Maud.

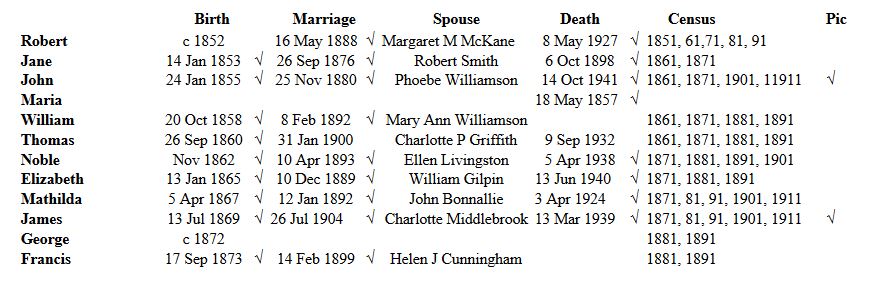

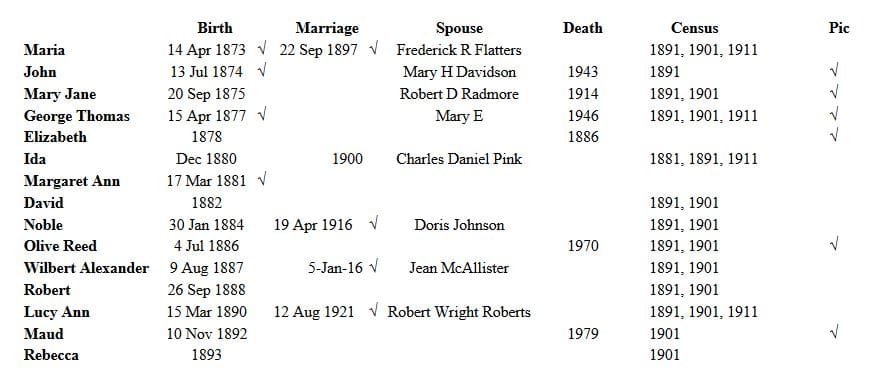

Noble Henderson and Mary Ann McCune had the following children:

Elizabeth Henderson and Robert Sissons

Elizabeth Henderson was born to John Henderson (1791-1864) and Elizabeth Brown (1797-1873) on November 10, 1834. She was married at the age of 30 to Robert Sissons (1848-1916), 14 years her junior, on June 27, 1898. Robert Sissons was born on January 4, 1848, the son of Thomas Sissons (1824-1905) and Jane Gilkison (1822-1905). Robert’s mother Jane (Gilkison) was the sister of Maria Emilie Gilkison (1832-1903) who married John Henderson (1821-1894). Elizabeth Henderson (1834-1881) and Robert Sissons (1848-1916) had four children. Elizabeth died at the age of 51 and is buried at St. Bartholomew’s Cemetery in Bourg Louis, Quebec. Their son Thomas (1876-1882),who died at age 6, is buried with his mother.Elizabeth and Robert’s daughter Jane married her first cousin, Adam Henderson (1872-), son of William Henderson (1828-1899) and Susannah McKinley (1829-1907). Robert Sissons remarried after Elizabeth’s death to Kathleen Hill (1871-1944), 23 years his junior, and they had at least eleven children together. Robert and Kathleen and two of their children are buried at Mount Hermon Cemetery, Quebec City. Robert Sissons wrote his last will on November 26, 1891 in which he is referred to as an”Esquire, Gentleman” residing at Lake St. Joseph in the Parish of Sainte Catherine. He mentions both wives in his will and essentially leaves 60 % of his property and goods to Kathleen Hill and 40% to his three daughters from his previous marriage to Elizabeth Henderson.

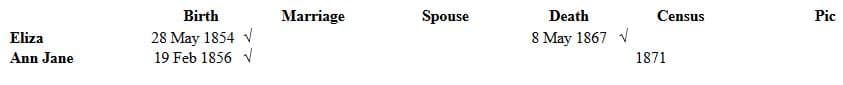

Elizabeth Henderson and Robert Sissons had the following children:

Thomas Henderson and Jane Smith

Thomas Henderson was born to John Henderson (1791-1864) and Elizabeth Brown (1797-1873) on February 23, 1837. Prior to his marriage, Thomas lived with his brother William (1828-1899) and assisted with the work on the farm. Thomas married Jane Smith (1839-1927) on March 11, 1861. Jane was born on December 18, 1839 at St. Gabriel, Valcartier, daughter of William Smith (1817-1897) from Yorkshire, England and Hannah Ireland (1814-1912) also from England.

Upon his marriage, Thomas owned a farm near Ste-Catherine. However, between 1878 and 1881, Thomas Henderson and Jane Smith moved to the village of Richmond, Quebec with their seven children where he became a “section man” for the railway. In 1891, Thomas and his family were living in the township of Pittsburgh,Ontario where he was a “section boss”. In 1901, Thomas and his family were living in the Cataraqui Ward in Kingston, where he was a “section foreman”.

Thomas and Jane had nine children, all of whom were born in the Valcartier area but one, Robert Herbert whowas born on February 18, 1882 in Richmond, Quebec. All their children survived to adulthood but one, Sarah Jane who died when she was one years old.

Thomas Henderson died on June 30, 1901 and is buried at the Cataraqui Cemetery in Kingston. Upon her husband’s death, Jane Smith resided with her daughter Ida (1867-1945) on Dundas Street in Trenton, Ontario and that is where she died on June 5, 1927. She is buried with Thomas at the Cataraqui Cemetery in Kingston.

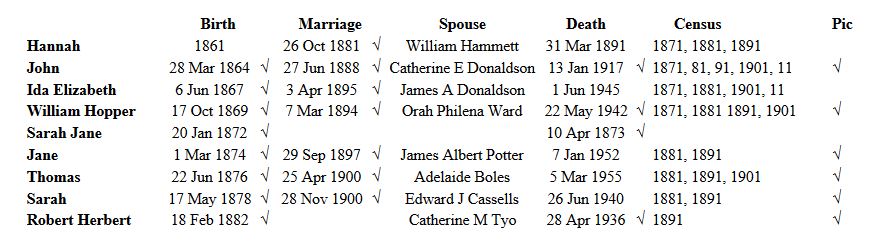

Thomas and Jane had the following children:

Ann Henderson and Hugh Boyd

Ann Henderson was born on May 12, 1839 to John Henderson (1791-1864) and Elizabeth Brown (1797-1873). Ann married Hugh Boyd (1834-1922), who was born at Ste Catherine, Quebec on February 2, 1834. Hugh Boyd was the son of Hugh Boyd (1788-1872) from Ireland and Catherine Stockman (1799-1881) also from Ireland.

Ann Henderson and Hugh Boyd (1834-1922), a farmer, married on September 25, 1871 at Christ Church in Valcartier. They farmed their entire life. Ann Henderson died on June 24, 1895 at the age of 56 at Ste-Catherine. Her husband Hugh died on July 7, 1922 also at Ste-Catherine, Quebec.

Their daughter Eliza Jane (1875-1954) married her first cousin, Thomas George Henderson (1877-1936), son of James Henderson (1830-1898) and Jane Ewing (1844-1936).

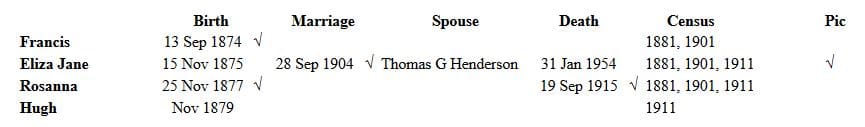

Ann and Hugh had the following children:

Margaret Henderson

Margaret was born to John Henderson (1791-1864) and Elizabeth Brown (1797-1873) on June 1, 1846. She died on March 26, 1849 when she was almost 3 years old.

Recent Comments